- Home

- Jeffrey Round

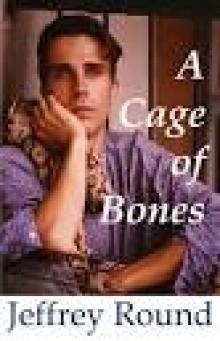

A Cage of Bones

A Cage of Bones Read online

Celebrating 10 years in print!

Praise for

A CAGE OF BONES

“I really enjoyed A Cage of Bones. It hits British culture and speech beautifully.”

DM Thomas, author of The White Hotel and Lady With a Laptop

“You can gauge the depth of my admiration when I tell you that my reaction to A Cage of Bones was simply envy.”

Douglas LePan, author of The Deserter and Macalister or Dying in the Dark

“Sexy and intelligent novel mixing fashion with politics. A Cage of Bones is A Room with a View for the gay 90s. It is hilariously funny but its social and political philosophy is astute.”

Kamal Al-Solaylee, Toronto Star Online

“Good bone structure!”

Kate Barker, Xtra!

Jeffrey Round is the author of The P-Town Murders, Death in Key West, The Honey Locust and Vanished In Vallarta. He worked briefly in the fashion industry and was the artistic director of Best Boys Productions, an independent theatre company. He was also the founding editor of The Church-Wellesley Review, Canada’s first annual journal for LGBT creative writing. His short film, My Heart Belongs To Daddy, won awards for Best Director and Best Use of Music.

Visit his website:

www.JeffreyRound.com

A CAGE OF BONES

Jeffrey Round

Rounder Publications

A Cage of Bones

World Copyright © 1997 Jeffrey Round

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or online reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is a work of fiction. In the interest of verisimilitude a number of actual organizations, periodicals and public figures have been mentioned. All have been used fictionally throughout. Any statements or situations ascribed to such are purely works of the imagination.

First published 1997 by GMP Publishers Ltd., UK.

Second edition © 2008 Jeffrey Round

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Round, Jeffrey

A Cage of Bones / Jeffrey Round. —

Second Edition

Originally published under ISBN 0854492526

ISBN 978-0-9810606-0-6

I. TITLE.

PS8635.O8625C33 2008 C813’.54 C2008-904847-4

In memoriam: Gianni Versace

1946-1997

For John James Davison, who showed

me that love is a gift, on his 33rd birthday

Here is my secret. It is very simple: only

with the heart can you see well. That which

is essential is invisible to the eye.

The Little Prince — Saint-Exupéry

A foreword by the author

As with many writers, the call to rewrite has always been strong in me. It’s the urge to perfect that haunts us and keeps us up at all hours—what Michael Chabon calls “the midnight disease.” When you think of it, though, are there any really perfect novels? Possibly not. While there are many great books and writers, the candidates for perfection—like sainthood—are few.

What is it about this sprawling, essentially rule-less genre that defies perfection? Perhaps it has less to do with the writing and more with how we as readers change over time. What we love today can just as easily bore us tomorrow. And while that shouldn’t change their “perfect-ness,” if they possess such a thing, a book that doesn’t engage us fully can’t really be called perfect even if everything about it is technically right.

Having said that, I’ve never thought A Cage of Bones was anywhere close to being perfect, but on its initial publication by The Gay Men’s Press in 1997, I was pleased with a great deal of it. And then I changed, as I am wont to do.

When I wrote (and lived) much of the book, I was in my twenties going on thirties. At the time, I was smitten with two writers: Marcel Proust, whose long-winded sentences dazzle with their construction, and Sylvia Plath, a pithy wordsmith whose poetry affected me more profoundly than any other poet except Shakespeare. Heady company—and in my youthful ambition I tried hard to measure up.

Reading A Cage of Bones now, more than ten years after its publication, proved illuminating. In the space of seconds I might pass from pride at what I’d accomplished to utter embarrassment at the book’s stylistic excess, not to mention the rigidity of its moral outlook.

You can’t erase the past, as my youthful protagonist Warden Fields discovers on his journey from pop icon through social pariah to liberated spirit. You can, however, edit books to conform to a greater sense of stylistic rigour, which is what I’ve attempted here.

On re-reading the book, two things were clear—my initial vision of the characters and their story still held a certain charm, and the basic writing was essentially sound, if a trifle flowery.

Nevertheless, I resolved not to edit so much that the book lost its appeal. It’s a story about young love, and I didn’t want it to lose its simplicity and directness. If the book was flawed, the flaws lay in its overly descriptive passages and a tendency to editorialize on the writer’s part. A description of a landscape is only valid inasmuch as it relates to the story. A moral note is only going to ring true when it’s dramatized effectively, not presented as a platitude.

Thus this descriptive passage from the first chapter of the novel’s original version:

Jagged peaks brooded in the distance among broken patches of cloud, resurrected out of their gothic existence. Sun glinted on powdery peaks in the thin air as the plane’s shadow rolled across a great sea of silver and black.

becomes this in the second edition:

Jagged peaks brooded among broken clouds, resurrected out of a gothic existence. Sun glinted on powdery crests as the plane’s shadow rolled across a sea of silver and black.

Thirty-nine words are reduced to twenty-nine words in the new version—roughly three-quarters of the original length—and that’s probably still too much poetry for some people.

When I got to the final chapter, I had a moment where I thought I might not be able to re-publish the book without substantial rewriting. It just seemed too flowery and I couldn’t see any way around it. For comparison, I re-read the ending of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, another book about the liberation of the spirit. To my surprise, I discovered Joyce’s ending was far more flowery than mine! With that in mind I pruned the last chapter but left it mostly as it was, hoping future readers would be more tolerant than me.

Apart from the stylistic trimming, the only major change in text concerns an event in the final chapter. In the book’s first edition, the character Rebekah Wentworth dies in a car accident (she’s noted as a risk-taking driver early on.) I included this at the urging of a well-meaning story editor who felt it would add emotional heft to the story, but it now reads to me as maudlin and melodramatic. The event as it occurs in this version is the one I wrote all those years ago and am happy to reinstate. It makes far more sense dramatically to me.

The only other change I made for the new edition was the cover. I was never happy with the GMP cover—not because the boy wasn’t sexy or attractive—he’s certainly that. My discontent lay in the fact that he didn’t look anything like the Warden I’d described in the book. An author’s qualms, of course. No one else seemed to mind.

And if the new cover raises cries of narcissism or egotism, I remind myself that those very qualities have made a career for more than one pop star. For that reason, I’m happy to use a photograph from my modeling days. And if I could edit myself to look

like that now, I would.

July 2008

A CAGE OF BONES

PART I

THE GEOGRAPHY OF DESTINY

1

From the windows of the plane he watched the coast of Europe spread below like a patchwork quilt—this region here, that mountain range over there. Blue mists and silver waters covered the earth. Warden checked his watch. Seven hours out of Toronto. The mid-Atlantic at dawn had been a lonely place. Now, craning his neck, he could make out hilltops and towns cradled in valley basins newly crowned by daylight. It was all fitting together piece by piece.

Up and down the aisles, passengers stretched tentative limbs as though unsure of the bodies they’d just awakened to. A bevy of blue-capped stewardesses dispensed steaming trays to anyone alert enough to want breakfast. It was remarkable to think he was on the other side of the Atlantic. He’d never left home before and suddenly he was halfway across the world. It occurred to him that life as he’d lived it—quiet, ordered and safe—no longer existed.

The previous summer Warden had been snagged from a beach full of rowdy volleyball players to portray the all-Canadian boy in a TV commercial. At the time, he’d had vague moral qualms over the superficiality of the pursuit. Still he went ahead, scoffing at the idea anything would come of it.

When the advertisement aired, he was amazed how his image took on an identity of its own, like an alien twin peering back from another dimension. Along with a rise in requests for dates, he also received offers from several established model agencies. One, Toronto Male, arranged a photography session for him, but school had started by then and he didn’t pursue it beyond that.

A few weeks later someone called to say his photographs were being sent to an affiliate group in Italy. The Italian agency contacted them to ask about his availability. He wrote to the head of the Italian group, a Sr. Calvino, thanking him for his interest and explaining he’d just started his second year at university and wasn’t available.

There was no reply. Then at Christmas Sr. Calvino telephoned him personally, urging him to come to Italy to work with his agency, Maura’s Models. Warden snickered at the name, thinking it someone’s awkward attempt at North American-casual. He refused, thanking Calvino again for the offer.

“But, darling—I want to make you rich and famous,” the voice oozed from the phone.

Warden laughed. The man’s accent was strange.

“Why do you laugh when I say that? Don’t you want to be rich and famous?” the voice asked petulantly.

“Right now, Sr. Calvino, I have to think about school.”

“But you have your whole life to read and study. Come to Italy. You would do so well here. Your face is very European.”

Warden wasn’t sure what he meant.

“You could have the entire continent at your feet!”

“I’m not sure I’d have room for it,” Warden joked.

The voice on the other end didn’t seem to catch the humour.

Warden relented. “I might have time in the summer,” he said, “but I’ll probably be working to make my tuition for next year.”

The voice exploded. “But, darling—work here! That’s what I’m telling you! You could be so rich. Why are you playing these games?”

“I’m not playing games, Sr. Calvino.”

“Well, then come by February at the very latest so we can work you in. In the summer it’s no good here—everyone goes to the seaside. Lazy, lazy,” he chided.

“I’ll be writing my mid-term exams in February,” Warden replied.

The voice sounded as though it had been stung. “Darling, you’re making things very difficult for me. Call me when you are ready to talk. I’ll be waiting.” Italy clicked off at the other end.

Warden went to the hallway and stood before the mirror. He turned his face this way and that, examining his features as though they belonged to someone else—sandy hair, high cheekbones and deep-set almond eyes. He could see nothing that would make anyone want him to travel all the way to Italy. Or anywhere else for that matter.

At supper he mentioned the call to his parents. It was one of the rare evenings his mother had come down to join them for supper. Beatrice looked hesitantly at her husband. Warden’s father thought it frivolous and said so. His sister, Lisa, however, declared it “most excellent” that someone from so far away should actually phone to ask him to join an agency.

“That’s so cool!” she said, her adolescent eyes flashing defiance. “Let geography be your destiny, Ward. Or you’ll always wish you’d done it when you had the chance.”

January passed. At reading week Warden came home with a bewildering pile of books. Another set of exams and papers and two more months of school lay ahead. Then another two years starting in the fall. He’d spent the last year and a half trying to convince himself the career path he’d chosen under his father’s tutelage had been a good one. He was no longer sure.

He tried studying at the dining table, but found it impossible to concentrate. Meaningless words danced on the page in front of his face. He closed his book and went for a walk. It was a typical February day, the ubiquitous greyness stretching on forever. The land and sky hovered between winter and spring, a dry rattling time of great opposition wearing through the winter-weary heart like tire tracks across fresh snow. People hurried by, clutching coats and hats to keep out the slicing cold. A bus tottered along with a cargo of pale discontented faces returning from the workday world like conscripts in a battle.

Warden cut across the park. Dead leaves hopped about in the wind like mischievous drunken birds where the snow had lain recently. He crossed a patch of brown matted grass and felt a twinge of loss. A chance forsaken. With the money left over from his commercial, he mused, he could probably go to Italy for a few weeks in summer. He might be able to afford it.

He thought of returning to school the following week, going back to his cramped dormitory room and the over-crowded lecture halls. He pictured the uneventful days that stretched ahead while a chill wind blew him across the field. A leaf fluttered in the air.

Warden looked over his shoulder. The sky lay in tattered rags along a dark horizon. Clouds were mounting over the lake, closing in with the night. Here and there daylight leaked through at the seams, small flashes of light at the edge of the sky like phantom gunfire.

Something moved inside him, looking for a face, a name. What was he yearning for? Whatever it was, he longed to grasp it and wrestle it to earth, far more than attending school or staying safe and secure within the confines of this, his home and native land.

He felt a shifting of forces, the tectonic plates of his being coming into play. Something had been calling him and at last he understood—it was life itself, that faceless, nameless desire urging him not to wait in hope or anticipation of a tomorrow that lay forever out of reach. He looked up and laughed. He would go to Italy. He’d have been a fool to miss it.

He ran all the way home, tearing into the house and bounding up the stairs to the room at the top. It had once been his room, a secret place where space invaders left blue powder stains on his pillow at night as evidence of their earthly visits, sustaining him through hours of fantasy. But when he moved into the dormitory, his mother had begun to spend more and more time there until they came to think of it as her room. He knew she’d be there.

Beatrice wasn’t sure precisely when she began to feel the pangs of fear and doubt that led her to withdraw from the world. They’d crept up on her gradually. At first it was only a desire to remain at home when the others went out. She liked the strong silence that invaded the house when she was alone—a silence replaced by a jumble of sounds from outside when the others returned from the skating rinks and movies and the million other worlds people belonged to momentarily when they left their homes and went out of doors. To prolong it when they returned, she retreated to the attic room under the eaves. Eventually the space between each succeeding trip to the outside—for that’s what they’d become, no longer did

Beatrice take simple walks to the post office or supermarket—became wider and wider. Sometimes the family didn’t see her for days at a time. They knew she was behind the door at the top of the stairs.

Warden knocked and went in. A canopied bed occupied the space along with a desk, a bookshelf, and a bearskin rug spread across the floor. His mother stood by the window overlooking the city skyline. What had she been watching? The lights scattered across the valley, perhaps, or the lines of cars snaking over the bridge in the twilight or possibly her own reflection pressed like a cloud upon all these things.

“I’ve come to tell you I’m leaving, Mom.”

“You’re going back to school tonight?”

Neat hair framed her oval face. Though still beautiful, her youthfulness had long since vanished, the features becoming more distinguished and isolated with time.

“I’m going to Italy.” He said it quietly.

She stood very still, as though inwardly folding and unfolding a fan. “But dear...when did you decide this?”

“Today. I mean, I think I’ve known it all along, but I made up my mind just now.”

The look she gave him wasn’t one of disapproval or objection, but simply concern that her child—or anyone’s child—might make a rash decision and live to regret it.

“Don’t you think you might take more time to decide, if you really want to go?” That wasn’t what she’d meant to say. Of all children, this one knew his mind before he spoke it. And once spoken, it was made up. “What about school? Have you given it proper consideration? I know you’re not happy with it…”

After the Horses

After the Horses Lion's Head Revisited

Lion's Head Revisited Shadow Puppet

Shadow Puppet Lake on the Mountain: A Dan Sharp Mystery

Lake on the Mountain: A Dan Sharp Mystery The God Game

The God Game Dan Sharp Mysteries 4-Book Bundle

Dan Sharp Mysteries 4-Book Bundle P'town Murders: A Bradford Fairfax Murder Mystery

P'town Murders: A Bradford Fairfax Murder Mystery Endgame

Endgame A Cage of Bones

A Cage of Bones